This week, the Los Angeles-based Craft & Folk Art Museum (CAFAM) will host the exhibit Displacements: The Craft Practices of Golnar Adili and Samira Yamin for its final weekend. Curated by Arash Saedinia, Displacements features the work of two young Iranian-American artists, Golnar Adili and Samira Yamin, and explores the subject of displacement in their respective family histories.

The pieces were created especially for this exhibit and make use of the intricate craft arts of paper cutting as well as hand stitching of photographs and documents from the artists’ family archives, telling their stories and giving the viewer a sense of a time in Iranian history filled with questions unanswered and a yearning for connection.

Yamin’s video installation “Scotoma,” named after the distortion of vision associated with migraines (something the artist personally experiences), is the only piece using animation in the exhibit. The animation involves cutting and rearranging pieces of a photograph with the use of Islamic sacred geometries. Curiously, the distortion is over her grandfather’s photo at the bottom right, but Yamin explains that in some works the arrangement of the pieces on the images is by coincidence.

“My scotomas almost exclusively begin just below right of the center of my field of vision, and expand from there,” she says. “Coincidentally, my grandfather, who passed away many years before my grandmother, is on the right side of the photograph, which meant the pattern would overtake his image first, so it was fortuitous that the representation of my scotoma also aligned with my personal history.”

When the Los Angeles-based artist heard her grandmother was sick in Iran, she decided to go back there to see her, which she was able to do before she passed away. It was there that she found the family archives– photographs of her grandparents, including her grandfather whom she didn’t know well.

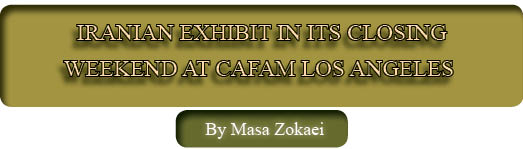

Photo Credit: Masa Zokaei

Previously, Yamin’s craft consisted of the use of photographs from books, newspapers and TIME Magazine, but in this case, while using images of her grandparents, she says, “I felt like the onus was entirely on me to make something aesthetically and conceptually compelling without being exploitative of the loss that is the impetus behind using them in the first place.”

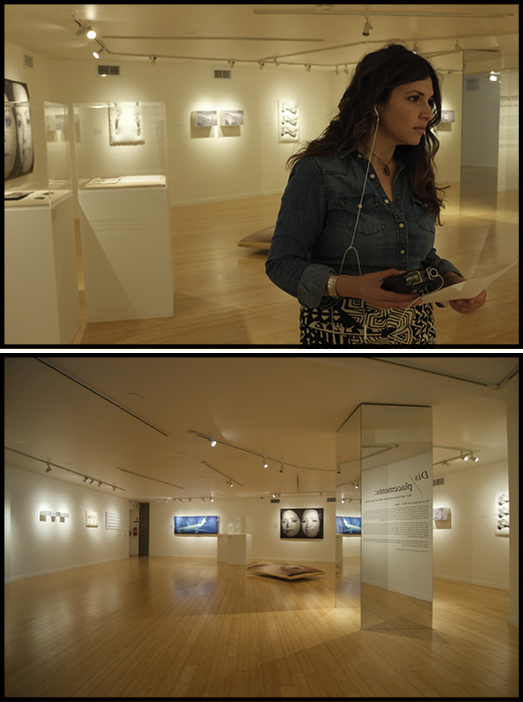

The works are site-specific and Yamin made use of the minimalist space of the museum with other photographs, specifically where she manipulated the light on images in frosted boxes filled with pieces of mirrors; a reference to the way the human eye uses reflection to view an image.

Golnar Adili utilizes a hand stitching practice with meaning in the patterns throughout the pieces in the exhibit, one of which is the most prominent in size, entitled “Shenasnameh” (meaning “tied it all together”). It shows two of her mother’s passport photos, which Adili had been carrying around with her for a long time, knowing she wanted to do something with them.

“The reason is the contrast between the two [photos], and knowing they encompassed the really anxious years of our moving around,” Adili says. “The contrast between the two spoke a thousand words.”

The photos are of her mother when she went back to Iran and when she returned three years later. They show a stark contrast of mood while illustrating a change: a colorful headscarf and, later, a dark headscarf accompanied by a serious expression. She was initially going to sew the title in Farsi as pattern on the piece, then decided to embroider on it the security pattern found on the pages of the passport, which you can see in person when looking closely at the intricate hand work.

Adili was out of the country when Hurricane Sandy hit, and her friends attempted to preserve what was in the flooded basement of her Brooklyn, New York, studio. It was then that she was forced to go through her father’s archives, something she found difficult to do before because of his passing at a young age.

Photo Credit: Arash Saedinia

And when working on these pieces, Adili recalls, “It is difficult in a cathartic way; it is necessary for healing purposes and ultimately very rewarding. It is my way of going through difficulties in life.”

Another work she did for the exhibit shows an image of her father’s arms pressed into bedding, symbolizing his absence when she was growing up as well as his deathbed in his struggle with cancer.

When Saedinia first saw the work of both artists before bringing them together for the exhibit, he was struck by the affinities between their practices. Samira at the time was working on the west coast, and Golnar on the east coast.

He says he was just the facilitator and had no say in the direction of their works, but that they came together very organically. He did, however, have hopes of what people would walk away with after seeing the exhibit.

“My hope was [that] a teenage Iranian-American who has never been to Iran [will] see compelling work by Iranian artists, and they see something that speaks to them on a number of levels, and they say, ‘Yeah we matter, and our stories matter—and it’s here in a museum,'” says Saedinia.

“Then the parents themselves see their experiences articulated in a way that is moving. I know that is the case because so many Iranians have experienced displacement.”

Adili had hoped that people who saw the exhibit could connect to the feeling of displacement through their own experiences, and, as she says, “deltangi”, or “missing a place, or a person.”

“I think that this is a running theme in many people’s lives,” Adili says. “I also wanted to give them exciting, and enticing visuals; something that made their eyes and hearts nourished.”

Displacements: The Craft Practices of Golnar Adili and Samira Yamin at CAFAM runs until April 27, 2014. Visit www.cafam.org for museum information.

Photo Credit: Masa Zokaei